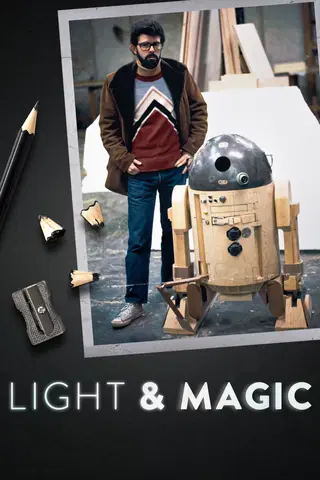

Gang of Outsiders

59min - The year is 1975, and George Lucas has a problem. He envisions his new film as a space opera, full of kinetic movement and speed. But with no special effects company in Hollywood capable of tackling his massive vision, George’s only choice is to start his own. Enter John Dykstra, camera expert, machinist, motorcyclist, pilot.

Dykstra begins assembling an unlikely team of artists, builders, and dreamers to join the newly christened Industrial Light and Magic. Setting up shop in an empty warehouse in Van Nuys, Dykstra puts in a call to camera operator Richard Edlund, whose colorful resume includes a stint in the Navy, rock and roll photography, cable car operator, and the invention of a popular guitar amplifier.

Meanwhile, a job posting for a “space movie” catches the eye of a young artist named Joe Johnston, who is desperate to cut down his commute time. The ensuing six-week offer to do storyboards is only complicated by the fact that Joe has no idea what a storyboard is.

News of the science fiction project in Van Nuys also attracts the interest of young effects enthusiasts Dennis Muren, Ken Ralston, and Phil Tippett. Admirers of Ray Harryhausen, all three have been making films since childhood. Upon reading the script for “The Star Wars,” Ralston marvels at the opportunity. Muren, however, simply thinks, “this is impossible.”

This “cabal of secret special effects people,” as George describes them, will prove uniquely suited to the task at hand. “I think he wanted a bunch of guys who didn’t know what was impossible,” says Joe Johnston.

Under John Dykstra’s leadership, the team sets to work creating a complex motion control system to allow the camera to repeat movements, a prototype of which Dykstra had pioneered in a series of experiments at the University of Berkeley.

As the months roll on, the team puts in eighteen-hour days at the warehouse in hundred-degree heat, occasionally letting off steam through slip n’ slide parties in the parking lot. Newly hired industrial designer Lorne Peterson blows the minds of his fellow model makers with a revolutionary new adhesive called superglue. “We were flying by the seat of our pants in a lot of ways,” Edlund recalls. For matte painter Harrison Ellenshaw, the culture shock of working at Disney by day and the ILM warehouse at night was jarring: “At Disney I was one of the youngest people, at ILM I was an old guy.”

Six months in, designing and building everything from scratch has proved much harder than anyone anticipated. The motion control prototypes are now complete, but the team has yet to produce a single piece of finished film. “We built this violin and now we had to learn how to play it,” Edlund explains. As principal photography wraps in England, the team scrambles to finish what they can. George returns to ILM, worn down by the stress of shooting, to find his team has only completed two shots out of the roughly four hundred needed. “I was… not happy,” George tells us.